NSHE Funding Formula 9: Comments on the Final Recommendations of the NSHE Ad Hoc Committee on Higher Education Funding

The NSHE Ad Hoc Committee on Higher Education Funding was authorized by AB493/2023, which provided a $2,000,000 appropriation for a study of the funding formula for NSHE. The Committee was convened by Interim Chancellor Patty Charlton and started meeting in November 2023 and finished its work on June 25, 2024. The Nevada Faculty Alliance actively engaged with the committee by providing information, analysis, and recommendations, as documented in this series of articles.

If the recommendations of the committee are fully implemented with no additional funding, there will be winners and losers—ranging from a gain of $7.6 million in state funding for CSN to a $5.8 million reduction for UNLV. In this article, we recap how the committee arrived at its decision and describe the major impacts on institutional budgets.

UPDATE [added 3/10/2025]: The final budget numbers presented by NSHE (page 24) at the pre-session budget hearings indicate larger redistributions of funding from UNLV ($9.8 million/year) and UNR ($11.0 million/year).

Public higher education in Nevada is underfunded overall, with total revenue per student FTE dead last among the 50 states. Nevertheless, the committee was charged with developing a new funding formula for the seven colleges and universities of NSHE without any new funding. That created a situation where the only possible way to increase funding for some institutions was to reduce funding for others, creating winners and losers. Although it was generally recognized that more support is needed for wrap-around services for at-risk and part-time students, adding a formula component based on student counts would necessarily reduce the component based on weighted student credit hours, which was designed to match the cost of instruction by level and discipline.

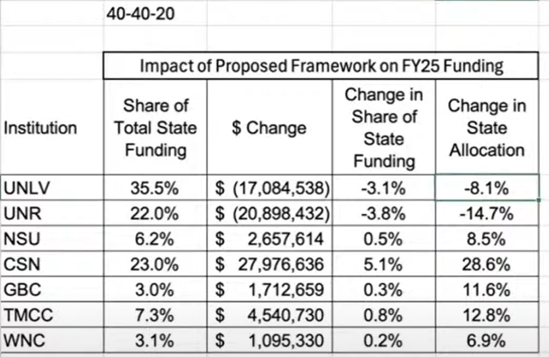

At its final work session meeting on June 25th (meeting video), the committee was tasked with making decisions on options provided by NSHE and its consultant, HCM Strategists. After decisions on various smaller decision points, the main decision was the percentage formula allocations to resident completed Weighted Student Credit Hours (WSCH,100% of the state appropriation distribution formula since 2014), Student-Based Funding (SBF, a combination of student headcounts and unweighted student credit hours, with extra counting for underrepresented minority students and Pell-eligible students), and Outcomes-Based funding (OBF, using a relative growth model as a replacement for the 20% Performance Pool carveout in the current formula). Using the consultant’s recommended allocation of 40%/40%/20% (WSCH/SBF/OBF) produced the following projected outcome:

Table 1. Impact of initially considered 40%/40%/20% WSCH/SBF/OBF funding model

This scenario would have resulted in severe budget cuts for the two comprehensive universities while significantly increasing funding for the community colleges. The committee members then looked for ways to mitigate the negative impacts. Throughout the committee’s deliberations over the past year, NFA and members of the committee indicated the need for new appropriations to fund formula enhancements or at least to provide hold-harmless funding. NFA’s recommendation for the percentage allocation was 75%/20%/5%, phased in over two biennia with new funding for the Outcomes-Based Funding component and hold-harmless funding for two biennia. Upon questioning from the committee, HCM Strategists admitted that their recommendations for the allocations percentages were arbitrary and not based on costs of providing the services or other quantifiable factors. That means the whole exercise was ultimately about shifting funding between institutions, i.e., selecting winners and losers.

In a key exchange during the committee’s deliberations on July 25th (video excerpt), member Betsy Fretwell cited the state revenue surplus according to the Economic Forum and suggested that $15 to $25 million in state hold-harmless funding was a reasonable request, seconded by Regent Stephanie Goodman. In response, Senator Marilyn Dondero Loop talked about all of the many budget needs of the states including pre-K to 12 education and stated that new funding for higher education from the Legislature could not be counted upon. Finally, Regent Carol Del Carlo pointed out that the only other source of funding is student fees and tuition, which the Board of Regents already indexes to inflation and raised by 5% last year to help cover cost-of-living increases that were mandated by the legislature but not fully funded.

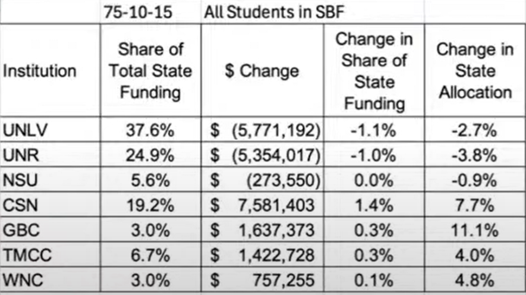

Following that discussion, the committee moved on to adjusting the proposal to reduce the negative impact on the universities, which also reduces the positive impacts on community colleges. They added non-resident students to the student-based funding component (which helps the universities that attract more out-of-state students) and ultimately changed the recommended percentage allocations to 75%/10%/15%. We emphasize that this is based on no additional funding; the modeling uses FY2025 appropriations and caseload and performance statistics, which will differ for the actual budget for 2025-2027. In addition, the committee recommended a maximum 3% reduction in any institution’s state appropriation for the first year of the new formula, which means UNR’s decrease would be slightly mediated and the difference spread proportionally among the other institutions.

Table 2: Impact of the final recommended 75%/10%/15% WSCH/SBF/OBF funding model

Breaking the recommended new formula down further, since the student-based funding component is half headcount and half unweighted student credit hours:

- 75% resident Weighted Student Credit Hours (100% in current formula)

- 5% resident and non-resident student headcounts, multiply counting underrepresented minority students and Pell-eligible students

- 5% resident and non-resident unweighted student credit hours, multiply counting underrepresented minority students and Pell-eligible students

- 15% Outcomes-Based Funding using the relative growth model

Another way to think about the 5% allocated to unweighted student credit hours is that it dilutes the weighting factors in the WSCH component, more so for institutions with more underrepresented minority and Pell-eligible students.

The relative growth model for Outcomes-Based Funding is based on the percentage growth in performance metrics for each institution relative to the prior year (reset each year), meaning that the institutions compete against each other for 15% of the state appropriations by maximizing annual growth in those metrics. The current Performance Pool metrics are targets that the institution must meet to receive its 20% budget carve-out. Those metrics are not necessarily appropriate for relative growth in outcomes because many are correlated with absolute enrollments and number of awards. The modeling used to calculate the Outcomes-Based Funding component largely followed the current WSCH-based allocations for the institutions, but that could change in the future as new metrics are set by the institutions as they compete against each other for this funding. The 15% allocation to OBF is therefore a wildcard that could cause budget volatility in the future.

The formula factors for each institution will be based on the higher of a 3-year average or the most recent year, rather than the single count year in the current formula. The committee also modestly increased the allocation for the Small Institution Factor, which benefits GBC and WNC. They recommended that a NSHE committee be formed to regularly review and update formula factors, including addressing other higher-needs students beyond underrepresented minorities and Pell-eligible students (for which data is available now), adjustments to weighting factors for the WSCH allocations, and any other formula issues. That could make the formula allocation a continual discussion.

The Small Institution Factor, which benefits Great Basin College and Western Nevada College, was increased from $30 to $40 per WSCH and the cap increased from 100,000 to 125,000. The effects are included in Table 2.

NFA's engagement and recommendations had a strong influence on the committee’s discussions, as acknowledged by the chair, Justice James Hardesty. A driving factor for the final recommendations was the committee’s reluctance to impose large reductions for the two research universities. The committee reduced the percentage allocated to Student-Based Funding (to 10%, versus 40% in the consultant’s recommendation and 20% in NFA’s recommendation). The result is a more modest proposal that still shifts funding from the universities to the community colleges. While NFA applauds increasing funding for the community colleges, including taking into account the services required to support their higher populations of part-time and at-risk students, we maintain that a new formula that merely redistributes existing funding is a failure.

The next step for the Committee is issuing its final report, which will go to the Legislature, Governor, and Board of Regents for consideration in the budget process for the 2025 session. NSHE’s budget request is due to the Governor at the end of August. The Governor and Legislature will make their own decisions regarding the Committee’s recommendations, which are advisory. NFA will be advocating for any implementation of the formula recommendations to be accompanied by new funding for the new student-based and outcomes-based formula components and, at a minimum, hold-harmless funding for at least two biennia.

The Committee, in part constrained by the charges given to it, did not take up the recommendations from NFA for a more fundamental change to the funding mechanism for NSHE. That would entail a transformation from a distribution formula to a true funding formula, where institutions are fully funded based on formula factors including inflation adjustments–rather than competing against each other for a fixed total appropriation, i.e., merely reslicing the funding pie. That is a missed opportunity for a win-win outcome.

In recognition that they did not have all of the information they needed to make their decisions, the Committee recommended that the remainder of the AB493 appropriation be used for an Adequacy and Equity Study of NSHE funding. If that use of the funds is approved by the State, NSHE will start that study in the coming months.

Finally, we would like to express our appreciation to chair Justice Hardesty and the members of the Committee for their dedication to improving higher education in Nevada, hard work, and consideration. They were given a difficult, if not impossible, task and forced to make decisions without all of the information that they felt they needed. Nevertheless, with NFA’s help, they managed to come to reasonable conclusions within the constraints imposed.

NFA Series on NSHE Funding Formula

Updated 8/9/2024 to include changes to the Small Institution Factor and link to the full meeting video. Edited 8/31/2024 to clarify that the current formula is based 100% on resident completed weighted student credit hours (WSCH).